|

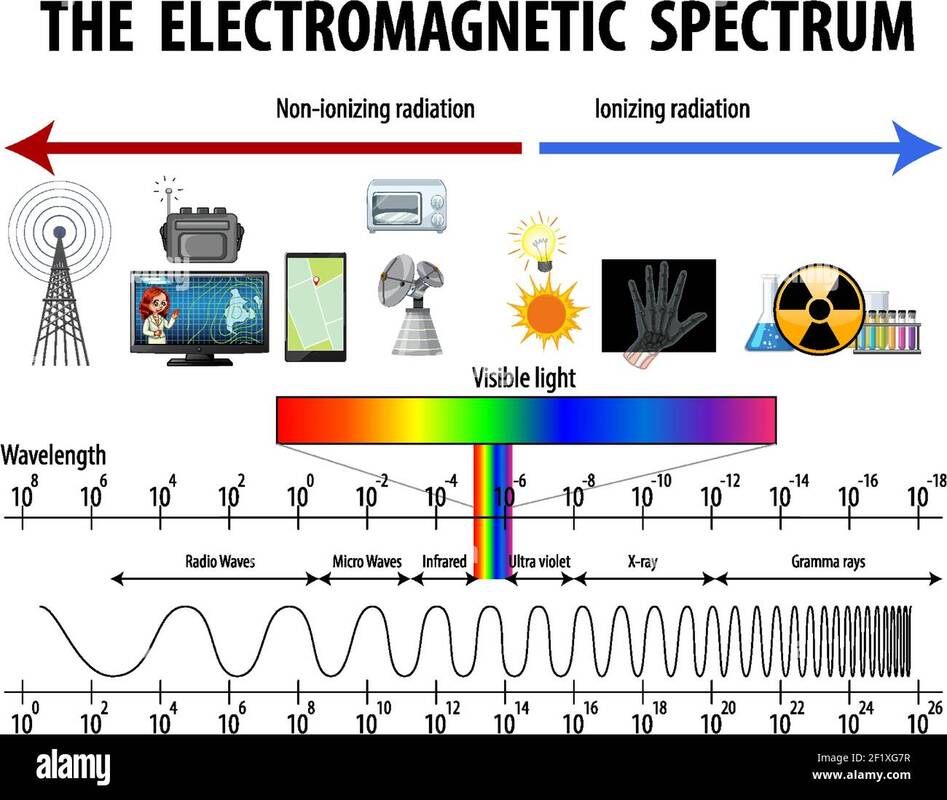

Consider the electromagnetic spectrum or that portion of it that is visible to our eyes. These are continuums.

Let us explore the concept of continuum as a conceptual tool. Take any two concepts that you wish to examine. Conjure up or take a piece of paper. Place one of the concepts on the ‘right’ side of the paper in relation to your perspective of that paper. Place the other concept on the ‘left’ side of the paper in relation to your perspective. Now, draw a line to connect those two points. I contend that those conceptual endpoints might be imaginary abstract descriptions of that concept, which might never be found in the world of experience at 100% of that descriptive definition. What you have drawn is a continuum where the two abstract points are now in a contextual relationship. Since we can only think of one contextual relationship at a time, to consider multiple contextual relationships concerning those two concepts, you need to create a parallel continuum and label that new continuum with the context you wish to consider as their interrelationship. The use of multiple and parallel continuums increases your ability to recognize nuances concerning the concepts that you wish to consider. Hypothetically, you can imagine those continuums not as parallel lines but as intersecting lines, those illustrating ‘dimensions’ of intersecting attributes/contexts. I contend that you can take this plane geometric mapping process and utilize it for any two concepts you wish to consider. Just remember that you are choosing to place each of the abstract terms you wish to consider at either end of that line. You choose which is placed at the rightmost end and which is at the leftmost end. Think about why you made those choices – they say something about your personal and/or cultural preferences. For example, take the concept of ‘black’ and ‘white’. Put black at the left endpoint and white at the right endpoint, with a connecting line in between those two endpoints. Label this the continuum of the amount of illumination that you experience at any one moment in time. Now, in the actual world of experience, do you ever experience 100% blackness- the complete absence of light? Or have you ever experienced 100% whiteness- the complete presence of light? That continuum illustrates the gradation of light that may be experienced at any one time, going from very dark to very bright with shades of ‘grayness’ in between. Or if you consider the continuum as the amount of pigment that you are mixing, then you have only black pigment at one end and only white pigment at the other end, with shades of gray laid out along the continuum. Another example. Take the concept of maleness and femaleness. Put femaleness at the left endpoint and maleness at the right endpoint and draw a line between them. Label this continuum of biological physiology. Draw another continuum and label this one sexual preference. What this gives you is a representation of the concept that you can be biologically male and have a sexual preference towards a male as one possibility of that sexual preference, or if you select what you call the middle of that line as the point that designates Bi-Sexual preference. We have now diagrammed it. You can now add a third parallel continuum and label it ‘self-definition of your gender’. Now consider one end of the continuum as having the attribute of activity and the other as having the attribute of inactiveness. Now consider one end of the continuum as having the attribute of hiding your emotions and the other end as displaying your emotions. Now consider one end of the continuum as thinking concretely and the other end as thinking abstractly. Now you have the ability to diagrammed out the possibility of being physically female on the one continuum, having a sexual preference of being Bisexual with a greater tendency toward the female preference since you placed yourself not exactly in the middle but somewhere beyond the midpoint and near one of the endpoints; on the other continuum, you could define your gender as masculine; on the other continuum as being someone who easily and often displays their emotions visibly; and lastly as being someone who thinks in very concrete terms. You have illustrated and designated yourself in multiple ways according to multiple possible cultural ways that the concepts of ‘male’ and ‘female’ have been described within that given culture. That is the potential utility of using continuums. Important caveat: you can list any number of conceptual pairs and place them in parallel lines. However, it may or may not be accurate to make the assumption that all the concepts on the same end of the continuum are actually in a significant and meaningful relationship. This means that you can make a continuum with the concept of Good and Evil and then go on to make another continuum of light skin tone and dark skin tone. You have now made those two continuums parallel to each other. However, just because you can do this doesn’t mean that there is a relationship between skin tone and Good and Evil values, as it is actually manifested in the world beyond your mental constructs. You must remember that you or your culture is making that assumption and imposing that assumption on those concepts. In general, associating value judgments and value continuums with some other conceptual paired continuum creates an assumption that is being imposed on those concepts by you or your culture. It may describe accurately how you and that culture feel about those concepts, but it does not make it a universal assumption or a valid and meaningful assumption.

0 Comments

I'm sure many of us grew up being taught by our parents and religious leaders that God is this all-knowing and all-powerful being and the creator of everything.

The things we are taught as a child shapes us and get locked up in our subconscious. Dwelling there, they become part of the emotional bias of how we see, feel, and think about the world. It is essential to recognize that these ingrained feelings are not proof that the ideas associated with them are verifiably true. All the feelings show is that you were influenced by those ideas at an earlier and impressionable age. Let's consider where those ideas of God being all-knowing and all-powerful came from. Throughout the TaNaK, the Hebrew Bible, the Divine is never credited as or described as All-Knowing and All-Powerful. This idea only shows up later in Rabbinic literature. The Rabbis' ideas and understanding of philosophy were powerfully influenced by the Greeks, specifically Plato and Aristotle. It is from Aristotle that the Rabbis got the idea of oppositional duality in general, specifically between humans and the Divine. The logic for Aristotle goes like this… We humans, and all of the physical world, are finite. Therefore, someone or something must be infinite. The finite changes. Therefore, some entity must be changeless. The finite is unstable and in flux. Therefore, some beings are forever the same, stable and constant. We lack knowledge, wisdom, and power. Therefore, someone must have all knowledge, all wisdom, and all power. We are many; therefore, this being who has all these attributes must be singular. Thus, Aristotle imagined the Unmoved mover, the one who started it all. The Divine One. Therefore, according to Aristotle, the opposite must manifest in something else. If we have finite knowledge, finite wisdom, and finite power, then there must, by Aristotelian logic and definitions, be an entity that has infinite knowledge, wisdom, and power. For Aristotle, this is the Creator, The Prime Mover, Plato's One, or Plato's The Good. That is where we and all of the Western cultures get the idea that God is all-knowing, all-wise, and all-powerful. It comes from Aristotle. From Aristotle and us, Christianity gets the same teaching. From us, Christianity, and Aristotle, Islam gets the same teaching. From the interaction and meeting of Christianity and Islam to the rest of the world, India's cultures, and China's culture – that is where they take on the same ideas of an all-knowing and all-powerful God. We were all taught this idea as children, and it all came from the oppositional dual thinking of Aristotle. But significantly, it does not mean it is true. We can determine what a thing is, its attributes, and its essence if the thing is physical. Then we can use our senses with any augmented tools to aid our senses in verifying a thing's attribute. Since God/Divine is not physical, its attributes can never be determined. We can only make them up and imagine what they might be. Thus, the idea that God/Divine is all-powerful and all-knowing is just some made up map and never can be anything but a made up map. It is merely Aristotle's map that has been incorporated into our understanding of God. However, we need to recall that a map is not the Territory. It is merely a human attempt to understand something. So, just because someone has invented such a map of God and has been accepted by so many people, that still does not make it verifiably true. It only makes it very popular. There have been others, like myself, who have described God, the Divine, as finite. For example, in his writings, William James also considered God as a limited and finite being with limited powers. God was obviously more powerful than us; it is just that James recognized that God was not all-powerful. On February 1, 1870, William James recorded the following in his diary:

I think that yesterday was a crisis in my life. I finished the first part of Renouvier’s second Essais and see no reason why his definition of free will—‘the sustaining of a thought because I choose to when I might have other thoughts’—need be the definition of an illusion. At any rate, I will assume for the present—until next year—that it is no illusion. My first act of free will shall be to believe in free will. [ (James, [son of William James] 1920, 147).][1] The above was quoted by Ralph Barton Perry, who wrote the famous work on the life and thought of William James, Perry goes on to comment on that quote: Thus James felt his old doubts to be dispelled by a new and revolutionary insight. It is important to note two things: first, the fact that he experienced a personal crisis that could be relieved only by a philosophical insight; and, second, the specific quality of the philosophy which his soul-sickness required. That he should have experienced such a crisis at all furnishes the best possible proof of James’s philosophical cast of mind. He had for many years brooded upon the nature of the universe and the destiny of man. Although the problem stimulated his curiosity and fascinated his intellect, it was at the same time a vital problem. He was looking for a solution that should be not merely tenable as judged by scientific standards, but at the same time propitious enough to live by. Philosophy was never, for James, a detached and dispassionate inquiry into truth; still less was it a form of amusement. It was a quest, the outcome of which was hopefully and fearfully apprehended by a soul on trial and awaiting its sentence.[2] Philosophy is, and should be, a playfully serious business—it should be taken up as if your life depends upon it—since it does. Here is how Albert Camus put it: There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy. All the rest—whether or not the world has three dimensions, whether the mind has nine or twelve categories—comes afterwards. These are games; one must first answer. And it is true as Nietzsche claims, that a philosopher, to deserve our respect, must preach by example, you can appreciate the importance of that reply, for it will precede the definitive act. These are facts the heart can feel; yet they call for careful study before they become clear to the intellect.[3] To choose to live, to get up out of bed each day is an act of free will and decision taken consciously or unconsciously, and it is a philosophic decision to affirm one’s ongoing life. Now for some getting out of bed is a mere habit and thus not an act or choice of philosophy or of free will. Free will is something, like self-awareness, that is only an ability that we have the potential to make use of. When we choose to think or act, consciously choose—that is an act of putting our potential for free will into operation and effect. Habit and habitual acts or the opposite of free will, they are acts taken by our unconscious to simply repeat what we have done before. Habitual thinking can be the enemy of free will and choice, it can be surrendering that potential for choice, though paradoxically we can consciously inculcate habits by choosing to make some action become repetitive and automatic. An artist or athlete relies on habit, depends on it, and has trained herself to utilize it as a means to accomplish her goals and purpose. To be an artist or an athlete is a choice, a life choice which can be a vocation, avocation, or if she is lucky, her profession. To become an artist or an athlete is to acquire skills and talents by the purposeful acquisition and work of inculcating habits. To practice over and over and over again an action or set of actions so that the body and the mind together will fix on a specific outcome when the time is ready and needed to act. That is what training to learn any skill is all about. To choose by free will to acquire a skill that becomes automatic and thus becomes a habit. Habits that you did not indeed to acquire are the opposite of free choice and free will. They are the results of circumstances shaping you. They could be the results of the shaping forces of nature, nurture, or culture. These kinds of habits are taken on unconsciously. They are maintained by the habitual decision processes of the unconscious mind. Getting out of bed, be it as a result of an alarm clock or just waking up seemingly without conscious choice, is an example of unconscious habit. Circumstances of your life got you trained to wake up as a way of responding to the alarm or to the rising ambient amount of light in the room or even your internal sense of time. William James wrote: But the fact is that our virtues are habits as our vices. All our life, so far as it has definite form, is but a mass of habits,--practical, emotional, and intellectual,--systematically organized for our weal or woe, and bearing us irresistibly toward our destiny, whatever the latter may be. … I believe that we are subject to the law of habit in consequence of the fact that we have bodies. The plasticity of the living matter of our nervous system, in short, is the reason why we do a thing with difficulty the first time, but soon do it more and more easily, and finally, with sufficient practice, do it semi-mechanically, or with hardly any consciousness at all.[4] James was right when he said, “So far as we are thus mere bundles of habit, we are stereotyped creatures, imitators and copiers of our past selves.[5]” That getting out of bed can be just the philosophic habit to unconsciously think that your life is worth living by the mere fact that you unconsciously choose not to think about your life and its circumstances and its meaning at all. Not in the way that either William James meant thinking or Albert Camus either. Living unconsciously by habit may be enough if you are lucky. Life will just enable you to avoid any crisis or challenge or change in circumstances and thus prevent your derailment from the habits of your life. But radical change, death of a friend or family member, pending divorce or separation or radical change in a relationship, serious accident, losing one’s job, etc., could bring about the questioning of your life situation and habits. These could cause an existential crisis—i.e. a philosophic crisis that makes you question how you have been living your life, which would require a philosophic response. You must answer the challenge and the question, is life, your current living situation, worth it. How you respond will either be an act of free will or not. You can either choose to do something consciously or not. If you consciously recognize the question and challenge and consciously choose a response, even if it is simply to say, ‘Well life must go on’, then you have demonstrated your capacity for free will. As you can see, free will is wrapped up with an act of conscious choice. It is the potential gift that we have if we avail ourselves of it. Those who deny we have such a capacity fail to understand themselves and others and prefer, unconsciously, to remain in a state of delusional determinism. Which is their unconscious choice and in general for such a person, they will refuse with all their might to consciously veer off from that belief. They will argue with vigor and intensity their denial of free will. That intensity and insistence by someone that we do not have free will seems to me to be a sign of their own belief which somehow, and for some reason, became wrapped up in their definition of life and self. It seems like they fear the responsibility of choice and thus they deny it. That denial will be disguised with such terms as ‘common sense’, ‘clear thinking’, and ‘realism’. But it is a denial of the reality that we potentially all have free will, we only need to choose to acknowledge it and use it. Works CitedCamus, Albert. The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays (translated from the French). Translated by Justin O'Brien. Vintage Books, a Division of Random House, 1955. James, [son of William James], Henry, ed. Letters of William James. Boston, 1920. James, William. Talks to Teachers On Psychology; and To Students On Some Of Life's Ideals. Dover Edition 1962, 2001. Henry Holt and Company, 1899. Perry, Ralph Barton. The Thought and Character of William James: As Revealed in Unpublished Correspondences and Notes, Together with his Published Writings. Vol. I. II vols. Little Brown, and Compnay, 1935. [1] (Perry 1935, 323) [2] (Perry 1935, 323) [3] (Camus 1955, 3) [4] (James 1899, 33) [5] (James 1899, 34) On February 1, 1870, William James recorded the following in his diary: I think that yesterday was a crisis in my life. I finished the first part of Renouvier’s second Essais and see no reason why his definition of free will—‘the sustaining of a thought because I choose to when I might have other thoughts’—need be the definition of an illusion. At any rate, I will assume for the present—until next year—that it is no illusion. My first act of free will shall be to believe in free will. [ (James, [son of William James] 1920, 147).][1] The above was quoted by Ralph Barton Perry, who wrote the famous work on the life and thought of William James, Perry goes on to comment on that quote: Thus James felt his old doubts to be dispelled by a new and revolutionary insight. It is important to note two things: first, the fact that he experienced a personal crisis that could be relieved only by a philosophical insight; and, second, the specific quality of the philosophy which his soul-sickness required. That he should have experienced such a crisis at all furnishes the best possible proof of James’s philosophical cast of mind. He had for many years brooded upon the nature of the universe and the destiny of man. Although the problem stimulated his curiosity and fascinated his intellect, it was at the same time a vital problem. He was looking for a solution that should be not merely tenable as judged by scientific standards, but at the same time propitious enough to live by. Philosophy was never, for James, a detached and dispassionate inquiry into truth; still less was it a form of amusement. It was a quest, the outcome of which was hopefully and fearfully apprehended by a soul on trial and awaiting its sentence.[2] Philosophy is, and should be, a playfully serious business—it should be taken up as if your life depends upon it—since it does. Here is how Albert Camus put it: There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy. All the rest—whether or not the world has three dimensions, whether the mind has nine or twelve categories—comes afterwards. These are games; one must first answer. And it is true as Nietzsche claims, that a philosopher, to deserve our respect, must preach by example, you can appreciate the importance of that reply, for it will precede the definitive act. These are facts the heart can feel; yet they call for careful study before they become clear to the intellect.[3] To choose to live, to get up out of bed each day is an act of free will and decision taken consciously or unconsciously, and it is a philosophic decision to affirm one’s ongoing life. Now for some getting out of bed is a mere habit and thus not an act or choice of philosophy or of free will. Free will is something, like self-awareness, that is only an ability that we have the potential to make use of. When we choose to think or act, consciously choose—that is an act of putting our potential for free will into operation and effect. Habit and habitual acts or the opposite of free will, they are acts taken by our unconscious to simply repeat what we have done before. Habitual thinking can be the enemy of free will and choice, it can be surrendering that potential for choice, though paradoxically we can consciously inculcate habits by choosing to make some action become repetitive and automatic. An artist or athlete relies on habit, depends on it, and has trained herself to utilize it as a means to accomplish her goals and purpose. To be an artist or an athlete is a choice, a life choice which can be a vocation, avocation, or if she is lucky, her profession. To become an artist or an athlete is to acquire skills and talents by the purposeful acquisition and work of inculcating habits. To practice over and over and over again an action or set of actions so that the body and the mind together will fix on a specific outcome when the time is ready and needed to act. That is what training to learn any skill is all about. To choose by free will to acquire a skill that becomes automatic and thus becomes a habit. Habits that you did not indeed to acquire are the opposite of free choice and free will. They are the results of circumstances shaping you. They could be the results of the shaping forces of nature, nurture, or culture. These kinds of habits are taken on unconsciously. They are maintained by the habitual decision processes of the unconscious mind. Getting out of bed, be it as a result of an alarm clock or just waking up seemingly without conscious choice, is an example of unconscious habit. Circumstances of your life got you trained to wake up as a way of responding to the alarm or to the rising ambient amount of light in the room or even your internal sense of time. William James wrote: But the fact is that our virtues are habits as our vices. All our life, so far as it has definite form, is but a mass of habits,--practical, emotional, and intellectual,--systematically organized for our weal or woe, and bearing us irresistibly toward our destiny, whatever the latter may be. … I believe that we are subject to the law of habit in consequence of the fact that we have bodies. The plasticity of the living matter of our nervous system, in short, is the reason why we do a thing with difficulty the first time, but soon do it more and more easily, and finally, with sufficient practice, do it semi-mechanically, or with hardly any consciousness at all.[4] James was right when he said, “So far as we are thus mere bundles of habit, we are stereotyped creatures, imitators and copiers of our past selves.[5]” That getting out of bed can be just the philosophic habit to unconsciously think that your life is worth living by the mere fact that you unconsciously choose not to think about your life and its circumstances and its meaning at all. Not in the way that either William James meant thinking or Albert Camus either. Living unconsciously by habit may be enough if you are lucky. Life will just enable you to avoid any crisis or challenge or change in circumstances and thus prevent your derailment from the habits of your life. But radical change, death of a friend or family member, pending divorce or separation or radical change in a relationship, serious accident, losing one’s job, etc., could bring about the questioning of your life situation and habits. These could cause an existential crisis—i.e. a philosophic crisis that makes you question how you have been living your life, which would require a philosophic response. You must answer the challenge and the question, is life, your current living situation, worth it. How you respond will either be an act of free will or not. You can either choose to do something consciously or not. If you consciously recognize the question and challenge and consciously choose a response, even if it is simply to say, ‘Well life must go on’, then you have demonstrated your capacity for free will. As you can see, free will is wrapped up with an act of conscious choice. It is the potential gift that we have if we avail ourselves of it. Those who deny we have such a capacity fail to understand themselves and others and prefer, unconsciously, to remain in a state of delusional determinism. Which is their unconscious choice and in general for such a person, they will refuse with all their might to consciously veer off from that belief. They will argue with vigor and intensity their denial of free will. That intensity and insistence by someone that we do not have free will seems to me to be a sign of their own belief which somehow, and for some reason, became wrapped up in their definition of life and self. It seems like they fear the responsibility of choice and thus they deny it. That denial will be disguised with such terms as ‘common sense’, ‘clear thinking’, and ‘realism’. But it is a denial of the reality that we potentially all have free will, we only need to choose to acknowledge it and use it. Works CitedCamus, Albert. The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays (translated from the French). Translated by Justin O'Brien. Vintage Books, a Division of Random House, 1955. James, [son of William James], Henry, ed. Letters of William James. Boston, 1920. James, William. Talks to Teachers On Psychology; and To Students On Some Of Life's Ideals. Dover Edition 1962, 2001. Henry Holt and Company, 1899. Perry, Ralph Barton. The Thought and Character of William James: As Revealed in Unpublished Correspondences and Notes, Together with his Published Writings. Vol. I. II vols. Little Brown, and Compnay, 1935. [1] (Perry 1935, 323) [2] (Perry 1935, 323) [3] (Camus 1955, 3) [4] (James 1899, 33) [5] (James 1899, 34) On February 1, 1870, William James recorded the following in his diary:

I think that yesterday was a crisis in my life. I finished the first part of Renouvier’s second Essais and see no reason why his definition of free will—‘the sustaining of a thought because I choose to when I might have other thoughts’—need be the definition of an illusion. At any rate, I will assume for the present—until next year—that it is no illusion. My first act of free will shall be to believe in free will. [ (James, [son of William James] 1920, 147).][1] The above was quoted by Ralph Barton Perry, who wrote the famous work on the life and thought of William James, Perry goes on to comment on that quote: Thus James felt his old doubts to be dispelled by a new and revolutionary insight. It is important to note two things: first, the fact that he experienced a personal crisis that could be relieved only by a philosophical insight; and, second, the specific quality of the philosophy which his soul-sickness required. That he should have experienced such a crisis at all furnishes the best possible proof of James’s philosophical cast of mind. He had for many years brooded upon the nature of the universe and the destiny of man. Although the problem stimulated his curiosity and fascinated his intellect, it was at the same time a vital problem. He was looking for a solution that should be not merely tenable as judged by scientific standards, but at the same time propitious enough to live by. Philosophy was never, for James, a detached and dispassionate inquiry into truth; still less was it a form of amusement. It was a quest, the outcome of which was hopefully and fearfully apprehended by a soul on trial and awaiting its sentence.[2] Philosophy is, and should be, a playfully serious business—it should be taken up as if your life depends upon it—since it does. Here is how Albert Camus put it: There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy. All the rest—whether or not the world has three dimensions, whether the mind has nine or twelve categories—comes afterwards. These are games; one must first answer. And it is true as Nietzsche claims, that a philosopher, to deserve our respect, must preach by example, you can appreciate the importance of that reply, for it will precede the definitive act. These are facts the heart can feel; yet they call for careful study before they become clear to the intellect.[3] To choose to live, to get up out of bed each day is an act of free will and decision taken consciously or unconsciously, and it is a philosophic decision to affirm one’s ongoing life. Now for some getting out of bed is a mere habit and thus not an act or choice of philosophy or of free will. Free will is something, like self-awareness, that is only an ability that we have the potential to make use of. When we choose to think or act, consciously choose—that is an act of putting our potential for free will into operation and effect. Habit and habitual acts or the opposite of free will, they are acts taken by our unconscious to simply repeat what we have done before. Habitual thinking can be the enemy of free will and choice, it can be surrendering that potential for choice, though paradoxically we can consciously inculcate habits by choosing to make some action become repetitive and automatic. An artist or athlete relies on habit, depends on it, and has trained herself to utilize it as a means to accomplish her goals and purpose. To be an artist or an athlete is a choice, a life choice which can be a vocation, avocation, or if she is lucky, her profession. To become an artist or an athlete is to acquire skills and talents by the purposeful acquisition and work of inculcating habits. To practice over and over and over again an action or set of actions so that the body and the mind together will fix on a specific outcome when the time is ready and needed to act. That is what training to learn any skill is all about. To choose by free will to acquire a skill that becomes automatic and thus becomes a habit. Habits that you did not indeed to acquire are the opposite of free choice and free will. They are the results of circumstances shaping you. They could be the results of the shaping forces of nature, nurture, or culture. These kinds of habits are taken on unconsciously. They are maintained by the habitual decision processes of the unconscious mind. Getting out of bed, be it as a result of an alarm clock or just waking up seemingly without conscious choice, is an example of unconscious habit. Circumstances of your life got you trained to wake up as a way of responding to the alarm or to the rising ambient amount of light in the room or even your internal sense of time. William James wrote: But the fact is that our virtues are habits as our vices. All our life, so far as it has definite form, is but a mass of habits,--practical, emotional, and intellectual,--systematically organized for our weal or woe, and bearing us irresistibly toward our destiny, whatever the latter may be. … I believe that we are subject to the law of habit in consequence of the fact that we have bodies. The plasticity of the living matter of our nervous system, in short, is the reason why we do a thing with difficulty the first time, but soon do it more and more easily, and finally, with sufficient practice, do it semi-mechanically, or with hardly any consciousness at all.[4] James was right when he said, “So far as we are thus mere bundles of habit, we are stereotyped creatures, imitators and copiers of our past selves.[5]” That getting out of bed can be just the philosophic habit to unconsciously think that your life is worth living by the mere fact that you unconsciously choose not to think about your life and its circumstances and its meaning at all. Not in the way that either William James meant thinking or Albert Camus either. Living unconsciously by habit may be enough if you are lucky. Life will just enable you to avoid any crisis or challenge or change in circumstances and thus prevent your derailment from the habits of your life. But radical change, death of a friend or family member, pending divorce or separation or radical change in a relationship, serious accident, losing one’s job, etc., could bring about the questioning of your life situation and habits. These could cause an existential crisis—i.e. a philosophic crisis that makes you question how you have been living your life, which would require a philosophic response. You must answer the challenge and the question, is life, your current living situation, worth it. How you respond will either be an act of free will or not. You can either choose to do something consciously or not. If you consciously recognize the question and challenge and consciously choose a response, even if it is simply to say, ‘Well life must go on’, then you have demonstrated your capacity for free will. As you can see, free will is wrapped up with an act of conscious choice. It is the potential gift that we have if we avail ourselves of it. Those who deny we have such a capacity fail to understand themselves and others and prefer, unconsciously, to remain in a state of delusional determinism. Which is their unconscious choice and in general for such a person, they will refuse with all their might to consciously veer off from that belief. They will argue with vigor and intensity their denial of free will. That intensity and insistence by someone that we do not have free will seems to me to be a sign of their own belief which somehow, and for some reason, became wrapped up in their definition of life and self. It seems like they fear the responsibility of choice and thus they deny it. That denial will be disguised with such terms as ‘common sense’, ‘clear thinking’, and ‘realism’. But it is a denial of the reality that we potentially all have free will, we only need to choose to acknowledge it and use it. Works CitedCamus, Albert. The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays (translated from the French). Translated by Justin O'Brien. Vintage Books, a Division of Random House, 1955. James, [son of William James], Henry, ed. Letters of William James. Boston, 1920. James, William. Talks to Teachers On Psychology; and To Students On Some Of Life's Ideals. Henry Holt and Company, 1899. Perry, Ralph Barton. The Thought and Character of William James: As Revealed in Unpublished Correspondences and Notes, Together with his Published Writings. Vol. I. II vols. Little Brown, and Compnay, 1935. [1] (Perry 1935, 323) [2] (Perry 1935, 323) [3] (Camus 1955, 3) [4] (James 1899, 49) [5] (James 1899, 50) The concept of Tikkun Olam is a unique rabbinic invention and it gives an individual and collective purpose to the Jewish people unlike, as far as I am aware, any other ‘major’ religious tradition worldwide. The goal is not for the individual to escape this world into a heavenly afterlife, or transcend this world into Nirvana or some other place of bliss. Rabbinic Judaism is I believe unique in that its goal is not self-centered solely on the desires and needs of the individual’s spiritual and psychological salvation and escape from this world.

The goal of Tikkun Olam is to heal not merely oneself, but the whole Cosmos, including the Divine Itself. It is to heal psychologically, spiritually, socially, politically, and ecologically this world and the universe itself. It is not to escape this physical realm but to improve it in the here and now. Tikkun Olam is a clarion call offering you a purpose a direction toward a meaningful life. The task is to find your way; your way to contribute to yourself and thus to life – to help yourself by helping others and everything. Not to sell yourself or sacrifice yourself but to do the difficult thing—to find a way to do what you can do in some ordinary way so that you can make a difference and feel that you have and are doing just that. When I wrote my book Find Your Way I started it off with a series of quotations. They seem like a good way to explain what I hope this book will provide for you and therefore give you a taste of what Tikkun Olam is all about. Unexpected invitations are dancing lessons from the Divine. (G. M. Jaron, 1970) That motto speaks to being open to unexpected possibilities of synchronicity. Synchronicity is a fancy word for coincidences that are meaningful. Finding yourself at the right place at the right time by just seeming happenstance. Be open to hope and believe that there is something out there that created everything and wishes us to work with us to fulfill its purpose and ours – together. It is not your duty to finish the work, but you are not at liberty to neglect it. (A saying from Rabbi Tarfon, 70-135 C.E., found in the Pirke Avot—the Sayings of Our Fathers. A portion of the Talmud. [2:16, Goldin, 1955, p. 116] The work is Tikkun Olam—meaning to heal, repair, restore harmony to the Cosmos, to oneself, and to the Divine. We are invited to participate in this great work. We are not expected to complete this task just to do what we can. Everything we do is part of this task. That is the belief that underlies the Kabbalah and thus my Qabalah. We affect the cosmos. So act with care and concern. You are not required to expend yourself beyond your capacity—just to find your way to fulfill and accomplish what you can and thus to contribute as best that you can. Traditional Jewish Kabbalah considered the doing of mitzvoth, such as keeping kosher, putting on tefillin, saying morning prayers, saying blessings at the appropriate times—when eating and drinking, seeing a rainbow, and other occurrences; all the normal ritual activities of a religious Jew were an act that had ripples into effecting a sefirah and thus added to restoring harmony to oneself, the Divine and thus to accomplish an act of Tikkun Olam. Clearly, this book is not being written to an observant Jew, and thus what am I talking about when I ask you to participate in Tikkun Olam? Well, I believe that all acts that increase the good, the true, the beautiful, and justice are acts that restore harmony in yourself, in society, and in the greater cosmos. If I am not for myself, who will be? If I am for myself alone, what am I? And if not now, when? (A saying from Rabbi Hillel, 110 BCE – 10 CE, found in the Pirke Avot. [1:14, Goldin, 1955, p. 69] It is important to acknowledge our unique self and what we can do for ourselves and thus for others. Only by helping and bringing ourselves into harmony can we participate to bring harmony to others and aid in Tikkun. We must recognize our own needs and those of the community – which ultimately is the community of humanity and this whole planet. We must start with ourselves. Appreciate ourselves and our abilities and uniqueness. Then we can help in the great work. But as the Hillel quote describes only doing work for yourself is not enough. All the self-help books and programs in the world are never enough. You are not here just for your self alone. You are never alone. Religions and spiritual practices that focus solely on your salvation are to me immensely selfish, and thus worthless. You are not born into this world to seek to leave it, the goal is not heaven or nirvana. Those are the goals of the selfish and self-centered. To obtain wealth and power and just to have it for oneself is evil and a waste. Hillel calls you to be more. To not just be for your self alone. You need to participate in your community and thus recognize that you are a citizen of the world, a participant in this ecological system of planet Earth. Therefore you owe it to society and this planet to do good, add to truth, add to beauty and add to justice for all. So political and social acts that you perform aid in Tikkun Olam. But do not think that political acts or recycling is the only way to contribute to social harmony. Every day and everywhere and with everyone you interact with is an opportunity to add to Tikkun Olam and thus to restore harmony. As the Zohar states in 2:263b ‘Invalid prayers, slander, angry words, belligerent deeds, and other things of this kind, reach “the other side” and strengthen its power.[1]’ Therefore the opposite is true. Be kind. Be patient. Be understanding. Make someone smile. Make someone laugh. All of this helps and it is a chance to do good. All mazim tovim—good deeds, are ways to contribute to Tikkun Olam. Always be aware and be ready to help someone in whatever way you can. Sometimes the little acts of kindness have the greatest effects of all. The unexamined life is not worth living. Socrates, 469-546 BCE, from Plato’s dialogue Apology, section 38a. You can not help others if you don’t understand who you are, why you are the way you are. You are a product of influences that shaped and molded you. Nature, nurture, and culture—the circumstances of your social and economic situation and context, all of this shaped you but did not fix and predetermine the outcome. The most difficult thing in life is to know thyself. Thales was the first of the Greek philosophers. 624-546 BCE. Diogenes Laertius attributed that saying to Thales, in Laertius’s book Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers. To take up the task and know how you came to be – this is important. To know your limits and your biases. How that process of shaping you has affected who you seem to be, this is what you need to figure out so that you can decide what to do with all the stuff—the ideas that were shoved down into your mind that shaped who you think you are. To examine ourselves – our life and our world so that you can make your life worthwhile for your self and for others, this is why you are here. To know what to do you must know who you are. A very difficult task. You are a mystery just as the cosmos is. Something to challenge you—a puzzle and a riddle—but it is never ever solved, not until your last life-breath is taken and your tasks and your potential for contributing is done. It seems to me that any [one[2]] who can…grasp the love of a “life according to nature” i.e. a life in which your individual will becomes so harmonized to nature’s will as cheerfully to acquiesce in whatever she assigns to you, know that you serve some purpose in her vast machinery which will never be revealed to you—any [one] who can do this will, I say, be a pleasing spectacle, no matter what [their] lot in life.[3] I believe that trying to understand yourself are acts that could restore your own inner harmony and thus contribute to your ability to act and add harmony to society, to the planet, to the cosmos as well. Not all those who wander are lost. J. R. R. Tolkien, The Fellowship of the Ring, Book I, Chapter 10, pg. 170 in the 2004 50th edition of The Lord of The Rings. Often we need to be willing to just wander about physically, mentally, and spiritually. Trusting that we will find our way. Knowing that with knowledge and faith in ourselves and the cosmos we will not be lost. Finding your way to help your self and thus give you the strength, the wisdom, and the ability to help in Tikkun Olam. May this book offer some means to guide you along the way. [1] (Tishby 1989, 2:511) [2] I will push William James’s thought beyond the limits of his unintended and unknowing cultural bias to push the language to refer to any and every one. [3] (Kaag 2020, 27) This quote was taken by Kaag from a letter William James wrote to his friend Thomas Ward in June of 1866. The context of that quote is this: I [William James] have thought of you [Thomas Ward] every day since I received it [referring to Ward’s letter]…and wanted to write to you; but having been in a pretty unsettled theoretical condition myself, from which I hoped some positive conclusions might emerge worthy to be presented to you as the last word on the Kosmos and the human soul, I deferred writing from day to day, thinking that better than to offer you the crude and premature spawning of my intelligence. In vain! The conclusions never have emerged…I began the other day to read the thoughts of Marcus Aurelius… …when we shall, I trust, patch up the Kosmos satisfactorily and rescue it from its present fragmentary condition. (Perry 1935, 230-231) In 1878 Henry Holt, the head of the publishing house Henry Holt and Company, made an offer to William James to write a text book on Psychology for Holt’s American Science series. It took James twelve years to write his book The Principles of Psychology, which finally was published in 1890.

It “quickly became an international bestseller, at least to the extant that a two-volume, 1,400 page, scholarly book could become a bestseller. (After two initial printings of 1,800 copies, there were three more printings by 1899*.” Shortly after James finished that book Holt requested James write a one volume abbreviated version as another more accessible textbook. In 1892 Psychology: The Briefer Course was published. That book went through six printings by 1900. *: pg vii-viii from David E. Leary’s The Routledge Guidebook to James’s Principles of Psychology, 2018, Routledge. William James was a wise thinker and demonstrated self-awareness by stating the limits of what he could present as verifiable in his books concerning the relationship of the body to the mind and the mind to the body. William James writes in his Principles of Psychology: Pg. vi Psychology, the science of finite individual minds, assumes as its data (1) thoughts and feelings, and (2) a physical world in time and space with which they coexist and which (3) they know. Of course these data themselves are discussable; but the discussion of them (as of other elements) is called metaphysics and falls outside the province of this book. This book, assuming that thoughts and feelings exist and are vehicles of knowledge, thereupon contends that psychology when she has ascertained the empirical correlations of the various sorts of thought or feeling with definite conditions of the brain, can go no farther—can go no farther, that is, as a natural science. If she goes farther she becomes metaphysical. …This book consequently rejects both the associationist* and the spiritualist** theories; and in this strictly positivistic point of view consists the only feature of it for which I feel tempted to claim originality. * Associationism is the idea that mental processes operate by the association of one mental state with its successor states. It holds that all mental processes are made up of discrete psychological elements and their combinations, which are believed to be made up of sensations or simple feelings. Members of the Associationist School, including John Locke, David Hume, David Hartley, Joseph Priestley, James Mill, John Stuart Mill, and Alexander Bain asserted that the principle applied to all or most mental processes. ** Spiritualist theorizes that mental phenomenon require an additional entity beyond the mind or the brain such as a Soul, or Transcendental Ego, or God. Pg 4 Bodily experiences, therefore, and more particularly brain-experiences, must take a place amongst those conditions of the mentallife of which Psychology need take account. Pg. 5 Our first conclusion, then, is that a certain amount of brain-physiology must be presupposed or included in Psychology. …it will be safe to lay down the general law that no mental modification ever occurs which is not accompanied or followed by a bodily change. From David E. Leary’s The Routledge Guidebook to James’s Principles of Psychology, 2018, Routledge. Pg. 44 Despite his use of ‘accompanied’ and ‘followed’ rather than ‘caused’, however, it must be admitted that James muddied the theoretical waters not only by slipping occasionally into interactionist language, but also, more radically, by seeming to move beyond mind-body dualism, as when he made bodily feelings a constitutive aspect of consciousness and personal identity (in Chs. 9 and 10) and portrayed the emotions in a way that virtually dissolved the separation of body and mind (in Ch. 25). In these and other instances, he was clearly foreshadowing developments in his later metaphysics (as presented in the first two essays in Essays in Radical Empiricism). The third and final assumption that provided the basis for James’s psychology was that mental states can and do know at least some physical states. Not only are mental and physical states related; some of their relations are cognitive. (Some are also emotional—emotions being for James a way of knowing by personal acquaintance, as the mind ‘inwardly welcomes or rejects’ its objects, as he put it in Principles of Psychology [in chapter VIII: The Relations of Minds to Other Things]. ------------ How the body gives rise to the workings of the mind is still a fascinating topic and books are continually being published to accomplish what James knew he could not do at his time. Examples of some excellent books on this topic are: Alva Noe’s Out of Our Heads: Why You Are Not Your Brain, and Other Lessons from the Biology of Consciousness, 2009, Hill and Wang. Antonio Damasio’s Self Comes to Mind: Constructing the Conscious Brain, 2010, Pantheon Books. D. T. Galbraith’s How Consciousness Came Into Being, 2012, Duddingston Books. Stanislas Dehaene’s Consciousness and the Brain: Deciphering How the Brain Codes Our Thoughts, 2014, Viking Penguin. When James says ‘truth is something that happens to a fact’ it means it doesn’t happen until someone says a fact is true at some place and some time. Otherwise and until that happens then the fact is just a part of the silent unspoken and unrecognized experience of reality and is not yet true.

You don’t seem to understand this. Let me quote you [I was having a discussion on Academia.com with H.G. Callaway]: “When and where people thought the Earth flat, it was in spite of that, and in the same times and places, not flat at all. If I say, for instance, the ancient Greeks developed no scientific recognition of biological evolution, then that one example shows that though true, the theory of evolution was not recognized. But are we to suppose that we are now in the lucky position of having recognized all the truths --so that none remain to be discovered? The concept of truth properly aligns with conceptions of an objective world which exists and has its effects whether we recognize it or not.” At the time of the ancient Greeks, according to James, biological evolution was not ‘true’. In that, no person knew this truth yet. Or when people such as the ancient Hebrews and Greeks thought it was a fact that the Earth was flat – that is what they believed. It was true for them at that time. It didn’t matter yet that the reality of the spherical nature of the Earth was something that was a fact – it hadn’t been recognized and thus as a human concept was not yet true. The ‘objective world’ can be experienced in all its non-verbal and non-symbolic nature as a percept, but we make concepts from this Territory and until we do that concept doesn’t exist. Until a person makes a specific map of the Territory that map doesn’t exist. It is only awaiting as a potential to be made by some person. I and James don’t agree with the statement that you can separate verification from the truth. Truth is found and made only in the process of verification. There is at any point in time always a way to verify aspects of the Territory – and truth and facts that are stated as being true only come to exist when someone makes that statement. There is always a way to try and make a claim, hypothesis, theory, map, etc as true. The attempt can always be made, however, the technology might not be up to the task. At the time of the ancient Greeks measuring the speed of a photon was possible – in theory, but they didn’t have the means or the conceptual map to attempt it and thus it was not yet a true fact. My statement concerning Newton was to point out James' pragmatic notion of how concepts can be made useful. Yes, Newtonian concepts are still treated as useful maps of the Territory even today. Newton’s underlying concept/map of gravity is no longer treated as a true map – but his concepts/maps are still pragmatically useful and thus according to James they hold some form of truth by that fact of their usefulness. ‘Truth happens…’ it always does and if the process of verification is not tried then that fact remains unproven and unverified. That is why I said an ‘unrecognized truth’ is an oxymoron for James. If it is not recognized by a person somewhere then that concept can not be claimed to be true. It only gets the label true when a person does recognize it through some process of verification. I came to study William James about five years ago. I first encountered James back in 1976-1977 while I was working on my BA in Religious Studies at the University of Washington in Seattle.

We were assigned James’s book The Varieties of Religious Experience. It was there that I first came across the idea of mystics and mystical experience. It was only in 2015/2016 that I had ventured into the used bookstore Moe’s that I came across a full set of William James’s books, including some of the major secondary sources. That began my intensive study of James. I have read all of his books and re-read a select few of them two or three times. I have been accumulating and reading many published secondary texts that have reviewed and explored James’s writings. I find him to be clear, insightful, and an extra-ordinary thinker who was ahead of his time. Alfred North Whitehead OM FRS FBA (born: 15 February 1861 – Died: 30 December 1947) was an English mathematician and philosopher. He is best known as the defining figure of the philosophical school known as process philosophy, which today has found application to a wide variety of disciplines, including ecology, theology, education, physics, biology, economics, and psychology, among other areas. In his early career, Whitehead wrote primarily on mathematics, logic, and physics. His most notable work in these fields is the three-volume Principia Mathematica (1910–1913), which he wrote with former student Bertrand Russell. Principia Mathematica is considered one of the twentieth century's most important works in mathematical logic and placed 23rd in a list of the top 100 English-language nonfiction books of the twentieth century by Modern Library. He later became interested in the history of philosophy and scientific endeavors and well as philosophy in general. In Whitehead’s book Modes of Thought, (Macmillian, 1938) within the first chapter, "Importance." Lecture One, he wrote this concerning the importance of William James: “In Western Literature there are four great thinkers, whose services to civilized thought rest largely upon their achievements in philosophical assemblage; though each of them made important contributions to the structure of philosophic system. These men are Plato, Aristotle, Leibniz, and William James. Plato grasped the importance of mathematical system; but his chief fame rests upon the wealth of profound suggestions scattered throughout his dialogues, suggestions half smothered by the archaic misconceptions of the age in which he lived. Aristotle systematized as he assembled. He inherited from Plato, imposing his own systematic structures. Leibniz inherited two thousand years of thought. He really did inherit more of the varied thoughts of his predecessors than any man before or since. His interests ranged from mathematics (pg 4) to divinity, and from divinity to political philosophy, and from political philosophy to physical science. These interests were backed by profound learning. There is a book to be written, and its title should be, 'The Mind of Leibniz'. Finally, there is William James, essentially a modern man. His mind was adequately based upon the learning of the past. But the essence of his greatness was his marvellous sensitivity to the ideas of the present. He knew the world in which he lived, by travel, by personal relations with its leading men, by the variety of his own studies. He systematized; but above all he assembled. His intellectual life was one protest against the dismissal of experience in the interest of system. He had discovered intuitively the great truth with which modern logic is now wrestling.” I agree with Whitehead's recognition of the importance of James. James was a genius, a deep and thoughtful thinker who tried to describe the big picture of humanly conceived and experienced reality as well as offering an understanding of how we think, feel, and experience that reality. He literally wrote the textbook on Psychology for the United States with his two-volume text The Principles of Psychology. He laid the foundation for a new school of thought which was inspired by but diverged significantly from, the writings of Charles Sanders Pierce. This newly developed system James called Pragmatism. James also laid another system of thought which involved the idea that James called ‘Pure Experience’ and it was the centerpiece of his conception of Radical Empiricism. James in print stated that these two systems should be evaluated on their own terms, but I, and others, see them as a unified and coherent vision. James did not write in a systematic and didactic style akin to Aristotle, James wrote in a style more reminiscent of Plato. Hence for many systematic philosophic thinkers then tend to dismiss or overlook James and instead go for Dewey or Pierce to discover an understanding of Pragmatism. This is a mistake. James laid out a clear system for those who are willing to read clearly and are open to unlocking seemingly contradictory statements by recognizing the subtle play and importance of context in James’s presentations. James understood that we believe what we need to in order to live a life that is meaningful for us. We will believe things on the basis of faith and trust. That the people we come to trust will tell us the truth. That they have checked things out and are relaying to us true facts about the way the world actually is. We expect our beliefs to match how the world actually is in reality. We make descriptions of our world which are metaphorically like making a map of the Territory that we are exploring. Humans make and make use of static finite maps of the infinite dynamic Territory. I use the term maps to refer to any symbol and/or symbol system that humans make as a result of their interaction with the Territory. Maps attempt to point towards, describe and understand the workings of things and events experienced via the senses. James’s idea of Radical Empiricism was the recognition that we are both and always a part of the external physical world and an observer of that world. Everything we understand about ourselves and the world around us comes to us through our experiences of ourselves and the world which is facilitated by our body’s sensory systems. The continuum of the Hard Sciences, such as physics, geology, astronomy, chemistry, and biology, etc., investigates and attempts to describe and understand inanimate objects and events, while the Soft Sciences, such as psychology, sociology, anthropology, zoology, etc., investigates animate objects and events. The middle ground between the two roughly corresponds to the category of plants and other non-mobile living things. For each of them, the more grounded in sensory observations the closer to verifiable accuracy a map will be. The less grounded the statements are in observations the more speculation is involved and the more the possibility that the statements cannot be verified with complete accuracy. The Hard Sciences create the most verifiable maps that point to the reality of how the world actually works. They make use of the most privileged human symbol system ever devised – mathematics, geometry, trigonometry, and calculus. These systems point toward the very structure of reality. The pragmatic success of science is found in the technologies that are the applications of the theories that sciences have to offer to explain the workings of the world. Technology usually is derived from the Hard Sciences. Technology proves that we can explain how the world actually works. Now science is a process and ongoing attempt to describe and understand the world and ourselves. Scientific theories, the maps of the Territory that scientists make, result in conclusions that are called facts. A fact is something that is known and proven about the world using the tools available to the scientists in a specific time and place. For example, Newton in 1704 could make a statement about the relationship of the light from the sun and come up with a result of a factual statement that was very specific. This statement could be verified and shown to be true using similar tools at that time. Now, with technological changes, a similar observation using the ideas described by Newton could be made today. The results should be different. This is what we should expect. New tools give us new insights. This does not mean that Newton made a false statement, it simply means that to believe today in Newton’s specific results would be to make a mistake. The principles that Newton laid out are still pragmatically useful. They still help to describe the world and its workings. It is just that Newton’s maps do not fully describe the Territory. No single map can ever do that. Every map needs to be verified continually. The difference in our results today is caused by the tools we have available today which Newton did not. So the results, the facts will change, but the principles, the theories of science at any time can still be useful guides to reality if they get results that can be verified using whatever tools we have at any specific point in time. To fail to understand this idea, that facts will change given the use of new tools, is to fail to understand how science works. The science of the past can guide us today if the theories, the maps, still point to how the world works despite the fact that the resulting numbers change with the use of new tools. Another example. Before Copernicus’s heliocentric theory of the relationship of the Earth and the Sun, people using a model that placed the Earth at the center of the solar system were still able to get pragmatically useful results. Their understanding of the relationship of the Earth and the Sun was in error but this did not prevent them from predicting eclipses or the positions of the planets and the stars as they observed them in the sky. They were able to make observations of the sky to aid in successful navigation on the seas. Thus the science of the day was pragmatically useful despite being mistaken in the underlying description of how the world worked. Thus demonstrating that science can be a pragmatically accurate system to map out the Territory when it can be shown to be valid utilizing the tools available at a specific time and place. If you get the results that your scientific theories expect at the time that you make the observations then your theories are shown to be valid at that time. If the results you expect are not the results you get then that theory has been shown and proven to be in error and needs to be corrected. A statement that cannot be verified is just an opinion or a faith statement. These do not necessarily describe or point to the reality of the external world. They can be important statements that can be inspiring and help to make life more meaningful. Hence James’s idea and defense of our beliefs in his essay entitled ‘The Will to Believe’. Here are some quotes from some of William James’s writing to describe his ideas. William James: Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking, 1907, Harvard University Press 1978 paperback edition Pg 96 Truth, as any dictionary will tell you, is a property of certain of our ideas. It means their ‘agreement’, as falsity means their disagreement, with ‘reality’. …Where our ideas cannot copy definitely their object, what does agreement with that object mean? Pg 97 Pragmatism…asks its usual question. ‘Grant an idea or belief to be true,’ it says, ‘what concrete difference will its being true make in anyone’s actual life? How will truth be realized? What experiences will be different from those which would obtain if the belief were false? What, in short, is the truth’s cash value in experiential terms? The moment pragmatism asks this question, it sees the answer: True ideas are those that we can assimilate, validate, corroborate and verify. False ideas are those that we cannot. This is the practical difference it makes to us to have true ideas; that, therefore, is the meaning of truth, for it is all that truth is known as. This thesis is what I have to defend. The truth of an idea is not a stagnant property inherent in it. Truth happens to an idea. It becomes true, is made true by events. Its verity is in fact an event, a process: the process namely of its verifying itself, its veri-fication. Its validity is the process of its valid-ation. But what do the words verification and validation themselves pragmatically mean? They again signify certain practical consequences of the verified and validated idea. Pg 101 Between the coercions of the sensible order and those of the ideal order, our minds is thus wedged tightly. Our ideas must agree with realities, be such realities concrete or abstract, be they facts or be they principles, under penalty of endless inconsistency and frustration. Pg 103 True ideas lead us into useful verbal and conceptual quarters as well as directly up to sensible termini. They lead to consistency, stability and flowing human intercourse. …all processes must lead to the face of directly verifying sensible experiences somewhere, which somebody’s ideas have copied. So, James is stating that there is a communal eternal reality that is available to us to experience via our bodily senses. What is true is events, objects, and interactions, processes that occur that someone, somewhere can experience with their sense or have done so. The foundation of all humanly experienced and conceived reality is based in and on our sensory experiences. Our bodies are directly part of reality and thus can directly offer information about reality. James coined the term ‘percepts’ for these events of experience. Then there are ideas that describe those experiences, those events and explain them. These James referred to as concepts. Many of those concepts/ideas can themselves be verified. Then finally there are ideas that can make a difference in our lives that we cannot verify but they make a difference in how we live our lives. These are ideas of faith, religious ideas, and ideals. They make a difference to us and they thus have a sense of truth in their utility to assist us to lead meaningful lives. This is where I derive my continuum of True and Truth, Fact and Faith. Something is true and is a fact if it can be verified. Something that inspires but can not be verified is a truth and a faith statement. From William James, Essays in Radical Empiricism, 1912, pp22-25, from the essay: Does ‘Consciousness Exist?’ “The two collections, first of its cohesive, and, second, of its loose associative, inevitably come to be contrasted. We call the first collection the system of external realities, in the midst of which the room, as ‘real’, exists; the other we call the stream of our internal thinking, in which, as a ‘mental image’, it for a moment floats. The room thus again gets counted twice over. It plays two different roles, being Gedanke and Gedachtes, the thought-of-an-object, and the object-thought-of, both in one; and all this without paradox or mystery, just as the same material thing may be both low and high, or small and great, or bad and good, because of its relations to opposite parts on an environing world. As ‘subjective’ we say the experience represents; as ‘objective’ it is represented. What represents and what is represented is here numerically the same; but we must remember that no dualism of being represented and representing resides in the experience per se. In its pure state, or when isolated, there is no self-splitting of it into consciousness and what the consciousness is ‘of’. Its subjectivity and objectivity are functional attributes solely, realized only when the experience is ‘taken’ i.e., talked-of, twice, considered along with its two differing contexts respectively, by a new retrospective experience, of which that whole past complication now forms the fresh content. The instant field of the present is at all times what I call the ‘pure experience’. It is only virtually or potentially either object or subject as yet. For the time being, it is plain, unqualified actuality, or existence, a simple that. In this naïf immediacy it is of course valid; it is there, we act upon it, and the doubling of it in retrospection into a state of mind and a reality intended thereby, is just one of the acts. The ‘state of mind’, first treated explicitly, as such in retrospection, will stand corrected or confirmed, and the retrospective experience in its turn will get a similar treatment; but the immediate experience in its passing is always ‘truth’, practical truth, something to act on, at is own movement. …Consciousness connotes a kind of external relation, and does not denote a special stuff or way of being. The peculiarity of our experiences, that they not only are, but are known, which their ‘conscious’ quality is invoked to explain, is better explained by their relations—these relations themselves being experiences—to one another. Were I now to go on to treat of the knowing of perceptual by conceptual experiences, it would again prove to be an affair of external relations. One experience would be the knower, the other the reality known; and I could perfectly well define, without the notion of ‘consciousness’, what the knowing actually and practically amounts to—leaning towards, namely, and terminating-in percepts, through a series of transitional experiences which the world supplies. William James: Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking, 1907, Harvard University Press 1978 paperback edition

Pg 96 Truth, as any dictionary will tell you, is a property of certain of our ideas. It means their ‘agreement’, as falsity means their disagreement, with ‘reality’. …Where our ideas cannot copy definitely their object, what does agreement with that object mean? Pg 97 Pragmatism…asks its usual question. ‘Grant an idea or belief to be true,’ it says, ‘what concrete difference will its being true make in anyone’s actual life? How will truth be realized? What experiences will be different from those which would obtain if the belief were false? What, in short, is the truth’s cash value in experiential terms? The moment pragmatism asks this question, it sees the answer: True ideas are those that we can assimilate, validate, corroborate and verify. False ideas are those that we cannot. This is the practical difference it makes to us to have true ideas; that, therefore, is the meaning of truth, for it is all that truth is known as. This thesis is what I have to defend. The truth of an idea is not a stagnant property inherent in it. Truth happens to an idea. It becomes true, is made true by events. Its verity is in fact an event, a process: the process namely of its verifying itself, its veri-fication. Its validity is the process of its valid-ation. But what do the words verification and validation themselves pragmatically mean? They again signify certain practical consequences of the verified and validated idea. Pg 101 Between the coercions of the sensible order and those of the ideal order, our minds is thus wedged tightly. Our ideas must agree with realities, be such realities concrete or abstract, be they facts or be they principles, under penalty of endless inconsistency and frustration. Pg 103 True ideas leads us into useful verbal and conceptual quarters as well as directly up to sensible termini. They lead to consistency, stability and flowing human intercourse. …all processes must lead to the face of directly verifying sensible experiences somewhere, which somebody’s ideas have copied. So, James is stating that there is a communal eternal reality that is available to us to experience via our bodily senses. What is true is events, objects and interactions, processes that occur that someone, somewhere can experience with their sense or had done so. Then there are ideas that describe those experiences, those events and to explain them. Those ideas can themselves be verified. Then finally there are ideas that can make a difference in our lives that we cannot verify but they make a difference in how we live our lives. These are ideas of faith, religious ideas and ideals. They make a difference to us and they thus have a sense of truth in their utility to assist us to lead meaningful lives. From William James, Essays in Radical Empiricism, 1912, pp22-25, from the essay: Does ‘Consciousness Exist?’

“The two collections, first of its cohesive, and, second, of its loose associative, inevitably come to be contrasted. We call the first collection the system of external realities, in the midst of which the room, as ‘real’, exists; the other we call the stream of our internal thinking, in which, as a ‘mental image’, it for a moment floats. The room thus again gets counted twice over. It plays two different roles, being Gedanke and Gedachtes, the thought-of-an-object, and the object-thought-of, both in one; and all this without paradox or mystery, just as the same material thing may be both low and high, or small and great, or bad and good, because of its relations to opposite parts on an environing world. As ‘subjective’ we say the experience represents; as ‘objective’ it is represented. What represents and what is represented is here numerically the same; but we must remember that no dualism of being represented and representing resides in the experience per se. In its pure state, or when isolated, there is no self-splitting of it into consciousness and what the consciousness is ‘of’. Its subjectivity and objectivity are functional attributes solely, realized only when the experience is ‘taken’ i.e., talked-of, twice, considered along with its two differing contexts respectively, by a new retrospective experience, of which that whole past complication now forms the fresh content. The instant field of the present is at all times what I call the ‘pure experience’. It is only virtually or potentially either object or subject as yet. For the time being, it is plain, unqualified actuality, or existence, a simple that. In this naïf immediacy it is of course valid; it is there, we act upon it, and the doubling of it in retrospection into a state of mind and a reality intended thereby, is just one of the acts. The ‘state of mind’, first treated explicitly, as such in retrospection, will stand corrected or confirmed, and the retrospective experience in its turn will get a similar treatment; but the immediate experience in its passing is always ‘truth’, practical truth, something to act on, at is own movement. …Consciousness connotes a kind of external relation, and does not denote a special stuff or way of being. The peculiarity of our experiences, that they not only are, but are known, which their ‘conscious’ quality is invoked to explain, is better explained by their relations—these relations themselves being experiences—to one another. Were I now to go on to treat of the knowing of perceptual by conceptual experiences, it would again prove to be an affair of external relations. One experience would be the knower, the other the reality known; and I could perfectly well define, without the notion of ‘consciousness’, what the knowing actually and practically amounts to—leaning towards, namely, and terminating-in percepts, through a series of transitional experiences which the world supplies. |

Gary Jaron

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed